Pedagogic Principles and Reflections Developing out of ISSRPL Practice

Adam B. Seligman

Temples have their sacred images, and we see what influence they have always had over a great part of mankind. But in truth the ideas and images in men’s minds are the invisible powers that constantly govern them, and to these they all, universally, pay a ready submission. It is therefore of the highest concernment that great care should be taken of the understanding, to conduct it aright in the search of knowledge and in the judgments it makes.—John Locke, Of the Conduct of the Understanding

The idea behind pedagogy at the International Summer School on Religion and Public Life (ISSRPL) is that knowledge is embodied. It is no doubt true that there can be no knowledge without some degree of generalization. Abstraction as such is built into the very use of words. Yet, there is also always a loss of certain types or modes of knowledge in this very generalization—even in the use of words. One of the ISSRPL’s aims is to minimize this process of abstraction and to convey certain “bits” of information as purely experiential date. This is why practicums, site visits, and the relocation of the school each year are such important parts of what we do. For ultimately we believe that our knowledge base is a mixture of what can and cannot be abstracted and generalized and even of what can and cannot be translated into language. It is for example just as important, if not more important, to see a member of the group with whom you have been together for two weeks rise up to take communion at Trinity Church in Boston, or some members separate from the group to partake in Muslim prayers in the mosque in Edirne, Turkey, as it is to read a chapter on Christian belief or Islamic worship. The experience serves to locate the act or acts (the prayer of one’s fellows) within a context that is not present in the written text. First, it locates it within the context of one’s own life. The praying Muslim or Jew or Christian is not a general, abstract other, it is Enver or Adam or David who is related to us in all sorts of complicated, contradictory and ultimately ungeneralizable ways. The general (category of praying Muslims or Jews or whatever the case may be) is given a particularity that a written text cannot, by definition (except perhaps in poetry), convey. This particularity gives it a presence, an aura or a “feel” that it would not have in its abstract categorization. Moreover, and because of this embodiment, the analytic place of this information within the body of our knowledge, within the “bits” of information that make up our understood world of Muslims, Jews, Episcopalians, or Catholics is different. The personal connection enhances the analytic framework of the knowledge, not just its affective contours (though to be sure the two are related) but also in a sense that the affective dimension itself adds to the analytic understanding by thickening the framework within which the particular “bit” of information is placed.

Thus, we learn that the categories that we usually use to parse experience and to explain the circumstances of our life are not the only possible or necessary ones. What is written in the books, newspapers, or passed on through our grandmothers’ stories are not the only ways to interpret or explain the world. In fact, a Muslim you see praying one the street might also be a basketball fan (a fact not usually pointed out in the New York Times articles on Islam or in the Italian textbooks). He and I can talk for hours about the Celtics, leading me to realize that my relationship to a Bosnian Muslim can be much more complicated and thick than I have always believed. He and I both relate to basketball, while he very much remains a Muslim and I a Jew. Do note that I am not saying here that we found a commonality, that is not the point (although it may also be the case), rather that we found a nexus of relationship that we would not otherwise have imagined, given the ways generalized knowledge is distilled and presented. The point is that we can come together, engage one another, around the topic of basketball (as we could if we were also, say, engaged in trade or building a cabinet) that is important here; not that we have discovered some point of common reference—some point of reference of self in alter or alter in self (basketball fandom). Although this later understanding is the most commonplace way of framing our shared interest in basketball, I believe it to be mistaken and potentially dangerous for it often leads us to believe that we have now discovered something that we “share” and that we can “scale up” from this shared bit of life to more and more shared attributes, interests, and desiderata. This however is a very risky process, almost certain to break down at the first serious economic downturn, political murder, or divergence of interests. It is useless to abstract a shared moral world from a common interest in basketball. However, if we understand basketball as a, albeit imagined, world where we do something together (exchange statistics of players, knowledge of team records, youthful, or not so youthful passions, etc.), then we begin to see the shared basketball as a space where we do things, rather than as an index of commonality. It is here, I posit, that a new way of living with what is different can be approached.

Creation of such a space forces contestation between it and existing bodies of knowledge, assumptions, cognitive grids and, ultimately collective conceptualizations that we have in our always-already-prepared toolkit of ideas and ways of dealing with reality. It is sometimes the case (though less so as we get older) that reading something forces us to reframe and rethink the sum of our existing conceptions, assumptions, and prejudices. But by and large, our existing body of knowledge is rarely challenged to the core by something we read. If contradictions occur between what we “know” and what we read, we usually find a relatively easy way out of the cognitive dissonance that results—most often by disclaiming or discounting the new bits of information, and it does not appear to be too difficult to do this. It is more difficult to do this with something we have ourselves experienced. The immediacy of the experience sets up a challenge to our already existing “wisdom” that makes life difficult precisely because it has the potential for upsetting our existing assumptions and turning the coherence of our world inside out.

None of this is to denigrate or minimize the importance of abstract and general knowledge. There is, of course, no civilization without general knowledge. But there is also no civilization if all particularities and individual histories, experiences, and insights are reduced to what is most abstract and communicable over distance; that is, to what can be digitalized and transmitted by an electronic file (by written text earlier). Any act of human creativity becomes a balance of the general and the unique, the abstract and the particular, the universalized and the embodied. The trick is to find the balance in whatever the given circumstances are. To a great extent, to too great extent, the knowledge valued and transmitted in the university tends to be only generalized and generalizable, abstract and universal in nature to an almost total disregard of the particular, unique, and singular—which is the experience of every one of us.

Part of this generalized default of the universities and the knowledge base it develops is rooted in the very mission of the universities to transmit knowledge in a manner that is cost effective, in fact, that is profit producing for the universities and which does not impinge on the ruling ideological definitions of personhood, separation of public and private realms, privatization of the good, and so on. One might ask why? For to transmit particular knowledge in particular forms is labor intensive and time consuming and involves a degree of commitment and inter-personal communication, trust, and sacrifice that liberal-individualist mass societies cannot ask of their members. It is much closer to what is communicated in a yeshiva or a madrassa or a monastery, which are dedicated to the reproduction of religious knowledge, indeed of a religious system that defines the most abstract and general in terms of the most personal and unique (God and the individual).

The pedagogic challenge then is to develop something approaching the practice of these religious institutions without the particularistic visions that accrue to them (i.e., their definitions of the sacred, regardless of their denomination). The challenge of the school is in fact, if we can develop an embodied pedagogic practice that is shared by members of different sacred traditions, that is, among those who do not share the fundamental terms of meaning? Perhaps one of the reasons the ISSRPL is so difficult and emotionally exhausting is precisely because of this aspect of its practice.

Where we are now in the development of the ISSRPL pedagogy is far from systematized. We are, in fact, engaged in a sort of ad hoc orchestration and coordination of the different visions rather than any attempt to “summarize,” “integrate,” and hence, generalize. We are in effect working toward some “rules of the road,” toward ways of allowing different terms of meaning and modes of explanation. So we have many particular voices raised, many idiosyncratic frames of knowledge presented and rather than adjudicating among them, we are trying to find a way to have them coexist. As we are dedicated to an enterprise that, by definition, resists systematization and generalization, we are constantly faced with the question of what we put instead. In slightly different terms we can say that the pedagogic problem of the school is: How can different truth claims coexist in a shared public space?

Generalization, of course, tends to reduce the difference. The particularities, which are precisely where the differences are felt, are relegated to the trivial, or lost completely (in some sense they become art and poetry). They are no longer assumed to be part of a shared knowledge base. The shared is precisely what is seen as generalizable. Of course what really happens is that the particular is not “lost,” it simply retreats into the private realm, into the synagogues, mosques, temples, and churches of the world. There, it continues to formulate the terms of meaning, the boundaries of trust and the most intimate grid of explanation for community members who live a “split screen” existence between what is shared in their general—now global—culture, and what is “really” shared, within each particularistic community. Often but not always, these are religious; for example, in the United States, race is a huge definition of particularistic terms of meaning, belonging, and experience, whereas in other countries, ethnicity plays this role; for example, Kurds in Turkey.

Here is where the group dynamics aspect of the ISSRPL begins to play such an important role. For “the group” is an attempt to model a broader society wherein these different particular interpretive grids are heard and are part of the group dynamic without being either generalized, or reduced into the purely individual, and idiosyncratic experience of each individual actor (which is the liberal-individual default that so many of the facilitators fall into without thinking and lose the point of the whole exercise).

In some sense, the real challenge of the school is to see whether we can take individuals from diverse context-rich communities, with different interpretive grids, and share a pedagogic experience without either turning everything into a form of generalized and context-free knowledge (the type we are so good at developing in the university context), or without reducing everything to the purely individual, liberal, and relatively atomistic vision of self and society. So far we seem to manage, albeit with great difficulty, exhaustion, and uncertain results. The task is to try to understand how we do this and perhaps produce a broad set of, admittedly, general rules of the road, for how this could be accomplished. If this is accomplished, we would have made some real progress toward understanding how to live together differently, a task I believe to be the overwhelming challenge of our new global order.

Perhaps the key has to do with explanation. David Hume pointed out that “Explanation is where the mind rests.” Thus, explanation is not the arrival at some ontological truth, or the “real” state of affairs, the final causal or prime mover of whatever event or sequence of events into which we are inquiring. This task is in fact, simply beyond our power as human beings. Rather, we deem a particular conundrum explained, when we cease—for whatever reason—to ask further questions. There is, we may note, something very pragmatist about this claim of David Hume (though 150 years or so avant la lettre). For when does the mind rest? Minds are, after all, very busy creatures always moving, questioning, and querying – people spend a lot of time doing yoga and meditating to get their mind to rest. When, indeed, does the mind rest? Most often it rests when the particular purpose of its questioning has been fulfilled.

For example, I may have a need to explain why the hammer is not in its proper place (because Joey forgot to return it after he made his workbox for shop) so as to be sure that next time it will be in its place (and I make a mental note to tell Joey in no uncertain terms to be sure to return my tools whenever he takes them). I do not need (or think I do not need) to know why Joey forgot to return the hammer (i.e., it is irrelevant for me if it is because his friend Pete called him out to play ball before he had finished cleaning up after he made the workbox or if it was because he came in for a glass of milk and dropped the bottle and slipped on the milk when cleaning it up and had to change his shirt and then his grandmother called, and so on. The endless regress of reasons is irrelevant for my purpose of making sure the hammer is always returned to its place after use. The mind rests when the purpose for which an explanation has been pursued has been met.

What then is the purpose for which we need explanation in much of our interaction with others? To answer this I would like to draw directly on the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey and his definition of an idea as “not some little psychical entity or piece of consciousness-stuff, but . . . the interpretation of the locally present environment in reference to its absent portion, that part to which it is referred as another part so as to give a view of the whole.”[i] An idea is a mental construct which frames and thus gives meaning (in Dewey’s terms, “interprets”) to a given and empirically present reality in terms of a set of factors not immediately present, but yet, by completing the picture of what is before me, serves to make it meaningful to me. Thus for example, I do not know what that guy from Bosnia is doing on the floor everyday at about 1:15, in the afternoon, but when I put it together with ideas I have about Muslim prayer (5 times a day, involving the salat) I can reach the conclusion that he is praying. What I am suggesting is that the explanation at which the mind rests, is in fact Dewey’s definition of idea. When we have an idea of something it generally means that we have explained it to our satisfaction. Our satisfaction is, in turn, determined by our ability to frame the given reality facing us (the guy from Bosnia on his knees) with sufficient supplementary information for us to know what to do (act respectfully toward him, or run to help him as perhaps he is suffering from internal bleeding in his stomach, or wait for further help to arrive . . . or as was actually enacted in a most macabre fashion in at least one U.S. airport, call the police, because it was feared as a prelude to a suicide bombing).

Explanation rests with an idea that we form of something; this idea is, according to Dewey, an amalgam of the currently available, physical reality before us together with additional, interpretive data that frames this reality in a broader, meaning giving context, defined by our specific purposes. Now there are certain types of action, particular tasks or sets of tasks such as studying for an examination, building a carburetor, preparing dinner, purchasing garden mulch, performing open-heart surgery, bidding on a stock option, ordering food in a restaurant, and so on, when it is relatively simple to see this process of explanation and idea formation at work. They are not our concern here. We are interested in a much more difficult task—to get at a set of ideas; those revolving around the self, the Other, and how to share social space with people who are very different from us and with whom we do not agree on what is most important to whom and what we are.

At its most successful, what the summer school allows us to recognize is that our ideas of these matters are very much what the French founder of sociology termed, “collective representations.” They are often not purely personal, idiosyncratic, and individual notions; rather, many of our ideas of our selves (or rather of the social part of our selves—and of the other—the part that is a Jew or a Muslim, a man or a woman, etc.) are manifestations of a collective conscience. They are collective ideas. In other words, in these matters (of our attitudes toward Jews or Christians or whites or blacks) the place at which the mind rests, is a collective place. As such, the purposes that they serve are collective ones as well.

Furthermore, these purposes are often not oriented toward opening ourselves, including our group selves, to alternative and sometimes challenging and conflicting definitions or understandings. Conversely, they are often geared to maintaining group boundaries, solidarity, and the sense of self and of self-righteousness. After all, the sense of who we are and why we are is very much a part of what makes up our collective representations and so our definitions of the situation—our ideas and explanations of any given event. These then come to constitute a grid, which we impose on experience. Explanation in fact, is not the beginning of experience, it is very much its end, it is the place where already-before-the-event, I know where I will locate it. One of the reasons that the summer school is so grueling is because we take apart these collective assumptions (of each of us) and agree to submit ourselves to working out a common mode of knowledge, interaction, and understanding with no such collective, a priori set of explanations predicated on the collective consciousness of each.

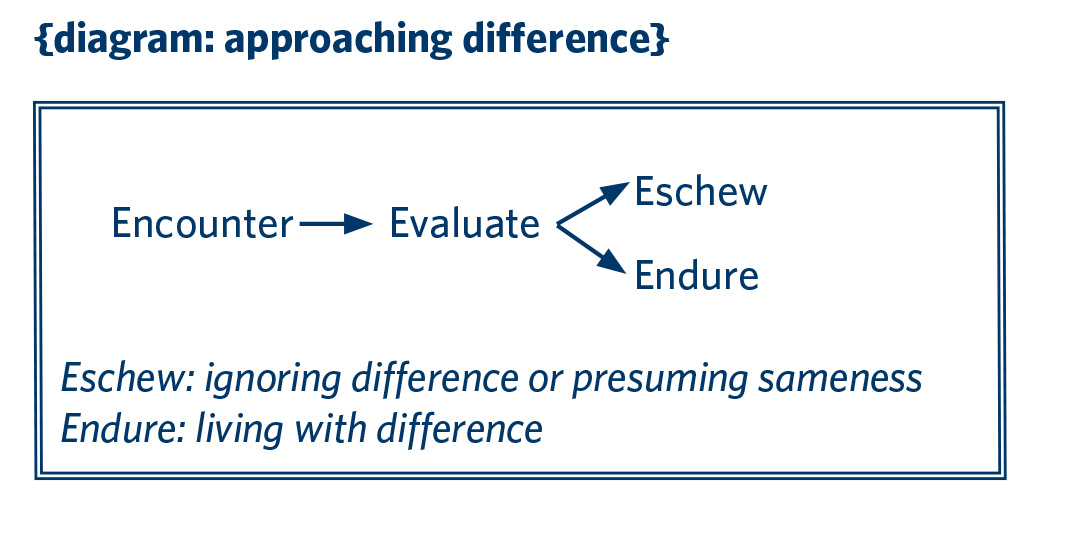

In essence then, what we do is eschew any final explanation; we agree to set apart broad, inclusive, and generalized explanations (and hence, à la Dewey, ideas). And although none of us questions our own belonging to such meaning-giving communities (which could be Jewish, Muslim, Christian, or secular-humanist) we are forced, by the environment of our shared time together, to eschew the types of explanations and ideas, precisely those interpretive frames to experience, that these would (and in other environments often do) provide to what we encounter together in these two weeks.

Agreeing to submit ourselves to this hiatus in explanation is no mean feat. It is extremely difficult and exhausting an exercise. It is, moreover, not something agreed on or formally declared before the start of our time together. In fact, the only “rule” we invoke is that we act “as if” no group, including our own has the monopoly on human suffering (this is true whether we are Jews, Palestinians, women, blacks, Armenians, or Kurds). This formal rule, which required no inner or sincere “assent,” is meant as no more than a traffic regulation to make continued interaction possible. However, the very need to adhere to this rule (whatever one feels inside) often (not always and not always consciously) has the consequence of forcing us to delay final judgment on events, people, and situations we encounter during the time together. In short, it forces reflection, what Dewey termed “reflective thinking.” Adhering to this rule (and it needs to be said that we do not always manage to do so, certainly not all the time), then contributes to a feeling of suspense, to our understanding of the situation as incomplete, doubtful and problematic. We admit lack of full knowledge, without yet accepting that we live in total ignorance and by blurring any absolute distinction between the two states we set up the possibility of “forming conjectures to guide action;” the very process that Dewey in fact described as the foundation of scientific thought.

I want to highlight the difficult nature of this endeavor, a difficulty which, in its general contours, was already discussed by Dewey. To quote him at some length, “Reflective thinking is always more or less troublesome because it involves overcoming the inertia that inclines one to accept suggestions at their face value; it involves the willingness to endure a condition of mental unrest and disturbance. Reflective thinking, in short, means judgment suspended during further inquiry, and suspense is likely to be somewhat painful. . . . To maintain a state of doubt and to carry on a systematic and protracted inquiry—these are the essentials of thinking.”[ii] This thinking through experience, suspending judgment even as one forms new conjectures leading us to new forms of action, is at the heart of the school’s work. We attempt this in only one very particular realm: that of our interactions with people we understand as different; that is, as sharing different terms of meaning, participate in different truth-communities, and who generalize trust and sense of belonging in very different ways. Not surprisingly it is precisely around these differences in religious belonging (between Christians and Muslims or Orthodox and Reform Jews) that the school orients its shared practice.

To refer back to the earlier quote by John Dewey, what we seek to arrive at through this suspension of judgment is that the “absent portion” of the “present environment” is no longer defined by the collective representations that each of us bring to the encounter. Or perhaps, more properly, when these representations are made public they are most often challenged and thus showed to have much more to do with the reality of the group making the interpretation (Muslims of Jews, Christians of Muslims, Orthodox Jews of secular Jews, etc.) than to any “objective” or “empirical” reality that is “out there”.[iii] This is the value gained by the suspension of judgment.

The understanding of this process is slow, cumulative, and not always conscious. What it necessitates is the experience of straddling boundaries. The individual retains his or her membership and terms of meaning as provided within their truth-communities, but comes to recognize the only partial, fragile, mutable, and heavily freighted nature of the interpretive frames that these memberships provide to events in the world; to realize, in fact, just how much these interpretive frames are marked by Bacon’s idols of the tribe, marketplace, cave or theatre.

What this makes possible is a redefinition of the purposes toward which explanation is oriented. The mind then, we can say, comes to rest in a different place. Distancing our collective representations of who we are and our own commitments to our own traditions from the process of idea formations and explanation in the particular and specific contexts of the school, allows us to redefine those purposes toward which explanation is oriented. These are no longer defined by the collective purposes of each participant’s own “in-group.”

We thus begin to localize our ideas and circumscribe our explanations toward what is most or more immediate without engaging our own particular collective philosophy of history, man, God, and existence. We learn to live, if not without the latter, at least without the latter forming the ground of each and every decision involving the other. By distancing these grand or meta interpretive grids from every environment in need of an explanation, we create a space where alternative and competing practices among members of differing and even mutually exclusive interpretive communities can construct a common life (even while remaining mutually exclusive in their truth-claims and all that follows from such). We learn to act (according to our newly formed conjectures and judgments) rather than react (according to our received prejudices and cognitive grids).

A concrete example is perhaps in order here. In the Jewish tradition, one of the fundamental principles regulating relations with gentiles is known as darchei shalom, the ways of peace. This is interpreted to mean that we must fulfill obligations of neighborliness with our gentile neighbors even if not explicitly commanded to; indeed, even when the written law absolves us of the obligation to treat the gentile neighbor in the same manner that we treat our Jewish brother. Most contemporary understandings of the darchei shalom principle interpret this behavior as purely prudential:: we act in such a way so the gentiles will have no reason to complain at Jewish behavior. However without such a concern there would be no need, for example to return lost property to a gentile. Such is the usual, “on the street” understanding of this term that one would find in many orthodox and ultra-orthodox synagogues. Yet, the fact remains that there is a great debate around the concept of darchei shalom and of the purely prudential understanding of its force. This debate goes back to the time of the Talmud (ca. 6 century CE). In fact, the Jewish tradition itself, from the Babylonian Talmud to more contemporary Halachic decisors, all recognize the problem with this very limited understanding of darchei shalom and thus offer a much thicker, richer, and value-laden interpretation of its obligatory nature. The point is, that one can find in the tradition, what one wishes to find and one’s scholarship will develop accordingly. Moreover, one may well be so under the sway of the idols of tribe or the cave, as to blind oneself to the richness of possible interpretations and understandings that the tradition permits, or even encourages.[iv] This is extremely relevant because often people standing with a tradition—be it Jewish, Catholic, Muslim, Hindu, or Protestant—claim to be obligated by their acceptance of transcendent dictates and revealed texts and that it is these obligations rather than any prejudice, failure of judgment, idols of tribe, marketplace cave, or grandmothers, which direct their behavior. What we are suggesting is that this is often not the case and one can very well accept and live comfortably within a heteronomously ordered tradition and still be open to experience and hence thought. Needless to say this is encompassed in the very meaning of halacha, or sha’aria—and was also the original meaning of the Christian religion—both of which mean way or path. For if all were finished, complete, and wholly assured no way would be called for, only a binary and in the nature of the case, finalizing decision, that would make all that followed meaningless.

This brings us to what I like to call the idea of embodied knowledge; that is, knowledge focused on particularities and hence what is, in essence, experience. Experience, as Dewey has taught us, is the central component in thinking. According to Dewey, “To learn from experience is to make a backward and forward connection between what we do to things and what we enjoy and suffer from things in consequence. Under such conditions, doing becomes a trying; an experiment with the world to find out what it is like.”[v] In this process, the intellect cannot be separated from experience and the attempt to do so leaves us with disembodied, abstract knowledge that all too often emphasizes “things” rather than the “relations or connections” between them.[vi] In so doing it is of precious little help in our attempt to connect the multitude of disconnected data that the world presents into a framework of meaning. Meaning, as is clear to all, rests not on the knowledge of “things” but on the relations between them. These relations, in turn, as Dewey so brilliantly argues, can only be assessed through experience because only through experience do we bring the relevant relations between things into any sensible sort of juxtaposition. Hence, the relevant relations between fabric, wood, staples, hammer, stain-pot, and brush are only made relevant in the construction of the chair. Without the experience of chair making, the relations between the components—even the definition of the component elements—is open to endless interpretation. Thus, meaning—emergent from experience can only be supplied by the goals toward which we aspire; as indeed, experience, as opposed to our simple passive subjugation to an event, is always in pursuit of a practical aim.

How then, one might ask, are these insights into the nature of experience and of thinking relevant to the practice and mission of the school? Having “bracketed out” or suspended our received impressions (of an abstract—and all too often, collective—nature) in the search of new judgments based on experience of a particular and embodied nature (the Muslim guy who likes basketball or the Jews who argue among themselves) can we say anything about this experience (of the school) that leads us to new types of judgments and conjectures? Can these new ideas (or even the process of arriving at them) in turn be formalized in any way and used as tools for further experiments in judgment formation outside of the school, and thus carried forward into other organizational settings and institutional arenas?

Perhaps the best way to answer these questions is to define the “backward and forward” motion that is achieved in the school. I consider the backward motion to be our existing preconceptions and uncritical knowledge base—often of a generalized nature, not tested by any real experience, only the received knowledge of the tribe, cave, market place, and so on. The forward motion is our continued process of conjecturing and idea-formation—now to be informed by the particular experiences of the school and not solely by the “received wisdom” of our respective communities (including, I must add, the community of liberal individualism, which, to no small extent, extends to that of the Western universities).

From this it becomes clear that the “thing” that we are acting upon and which in turn is acting upon us is not a block of wood or a screwdriver, nor the deciphering of a text or of a problem in geometry; but rather the “thing” is our ideas of ourselves in relation to people who are different from us. A small matter it would seem, when put so simply. Yet it goes to the core of our existence, both as individual egos and as members of collectivities. Whether we turn to the problems of ego’s differentiation from mother or of collectivity’s struggles to maintain their existence over time, the problem of self and world (which is the problem of the self and the non-self, or of self and what is different from self) is, in fact, one of the defining problems of existence.

The individual/psychological aspect is relevant here; for what we have learned from D.W. Winnicott, Marion Milner, and other object-relation theorists is how important it is to have the capacity to, at times, posit the relations between self and world with a certain degree of “fuzziness” or indeterminacy. Winnicott’s work on the “transitional object”—the object (e.g., child’s teddy or blanket) whose origins is never questioned, which thus remains curiously undefined and which in turn allows the ego (self) to differentiate from mother and so to actually perceive the existence of mother as a separate entity is a case in point. It is not coincidental, that when Marion Milner comes to discuss the very ability of ego to perceive the other as external object she repeatedly comes back to the loss of ego boundaries—that is of boundaries between ego and object as one necessary stage in the development of such apperception. The very “confounding of one thing with another, this not discriminating, is also the basis of generalization,” the basis—as she goes on to quote Wordsworth—of the poet’s ability to find “the familiar in the unfamiliar.”[vii] Generalization, which is a necessary component of empathy, itself rests, as pointed out by Ernst Jones, on a prior failure to discriminate, a prior tendency to note identity in differences.[viii] Again, boundaries blurred and reconstituted. Moreover, the ability, says Milner “to find the familiar in the unfamiliar, require[s] an ability to tolerate a temporary loss of sense of self, a temporary giving up of the discriminating ego which stands apart and tries to see things objectively and rationally.”[ix]

I would suggest that the “temporary giving up of the discriminating ego” is on a par with what Dewey was referring to when he discussed the painful process of suspending judgment and living in the suspense that results. By suspending judgment, I am, after all, suspending one of the prime activities of the “discriminating ego.” Holding judgment in abeyance, I am in effect reigning in the ego’s will to dominate through explanation the given situation. There are to be sure situations, such as erotic attachments, where the pain of this suspended judgment is mitigated or replaced with pleasure; what we must learn to do more consciously is to suspend judgment even when the immediate benefits do not seem to outweigh the loss.[x] This is one important pedagogic role of the school. The critical analytic point to make is that fuzziness of boundaries is a result of suspended judgment. Labile boundaries—boundaries that exist, but are not absolute—are a function of suspended judgment. One recognizes that judgment must play a role in organizing our relation to the world and in structuring our activities (hence the positing of boundaries) but, at the same time, one temporarily suspends judgment (thus blurring the boundaries) about certain aspects of the relation between self and world.

This, what we may term, “boundarywork” comes to play a not insignificant role in the education toward empathy, resting as it does on a decentred self, and on an ability to generalize out, beyond one’s own experiences. For such to take place, boundaries must in some sense be fuzzy and less than strict and fully discriminate, even when judgment is, in many cases, suspended.

This long aside into individual psychological traits is important as it helps to clarify for us another and critical dimension of the Deweian insight regarding suspended judgment: such suspended judgment reorients us toward our own boundaries (essentially those between self and non-self, whether on the individual or collective level) and brings a certain fuzziness to bear on our relation to these boundaries—a fuzziness where empathy, tolerance, and a new attitude toward the non-self can be developed.

One critical component of this process, especially in our own attempts to understand its working along collective lines is the role of symbols. Symbols act as mediums, intervening substances (transitional objects) that, in blurring boundaries between ego and object, make possible to eventually perceive objects outside of ego. Symbols, as transitional objects, are the critical link that allows us to perceive Other, through a process of not quite incorporating Other within our internal space. They allow both the blurring of boundaries and their reconstitution, analogous to what Winnicott claimed for the transitional object and, indeed, for all acts of creative play. In the context of the problematique of the summer school, the symbols referred to are not crosses, flags, or six pointed stars, but they are the very ideas we form that place “where the mind rests,” in our regard of the Other. Although not reducible to an image, they nevertheless provide a code or grid, framing both ourselves and alter in a web of significance and meaning. In Deweian terms, we are thus referring to those ideas, which provide the supplementary information we need to make sense (i.e., explain) our meeting with the Other.

Symbol systems thus function as mediating structures, transitional objects that mediate the relation between self and world (essentially the role of culture). But, if we return to our example of the Jewish laws of relations with gentiles discussed above, we see that these systems are themselves open to endless interpretation and divergent understandings, their own boundaries are fluid, to be determined by the conjectures, judgments, and goals that define the situation within which they are invoked. Yes, they may well mediate our relation with the world, but let us not confuse that with defining either us or the world. Holding such definitions in abeyance (a process which demands the suspension of judgment, the mental pain of such suspension, and the blurring of boundaries) allows a malleability in our approach to these cultural (and hence by definition, collective) systems that, in turn, permits –a thinking through of our relations to the Other, which is not otherwise possible. New conjectures, new judgments, a new experience of thinking is now possible, as the experience of difference is disembodied from existing judgments, conjectures, and “idols.”

If we follow the logic of the preceding argument, empathy and the tolerance of difference must, if they are to be long lasting and constitutive of our practice, rest on the very type of duality between boundaries and their dissolution and for which certain types of iterated activity may provide an important propaedeutic. They must, we are claiming, arise as conjectures born from experience, rather than as a particular ideological position, or a priori interpretive framework such as one stemming from the received wisdom of liberal-individualist precepts, for example. In a word, they must be born of experience, rather than ideology. John Dewey has claimed that “ideas are not genuine ideas unless they are tools in a reflective examination which tends to solve a problem.”[xi] Characteristic of such ideas are “a willingness to hold final selection in suspense [as well as] alertness, flexibility, curiosity.” In contrast, “dogmatism, rigidity, prejudice, caprice, arising from routine, passion and flippancy are fatal”.[xii]

The school attempts to provide a framework where the framing of such ideas (as opposed to ideological positions, (however “benign”) can take place. We do this through a particular approach to the perennial challenges of collective action. These challenges, (i.e., problems that all human collectivities must solve) include: (1) the organization of the division of labor; (2) the generalization of trust beyond (and for that matter within) primal units; and (3) the provision of meaning. The summer school creates an environment where one of these components of social order is understood as shared, one is understood as not shared at all, and the challenge, within these conditions, is to generate the third. To put it more explicitly: the “division of labor” is shared. It can be understood as all of the collective activities that we do together (and we do almost everything together). These include lectures, preparation for lectures, trips, visiting different houses of worship, practicums, meals, providing for the religious needs of different communal members (Jews, Muslims, Christians, including not only prayer service and times, but also special meals), organizing time together, and coordinating different needs.

The “provision of meaning” is understood as the very different religious and sacred commitments of the group members, which may prevent them from eating the same food as other members, traveling on the same days, or interpreting events, actions, and beliefs in the same way. Mention should be made that in such situations as the ISSRPL, the default of group participants is always to hide or deemphasize what is different and highlight what is shared among them. This is understandable and to an extent necessary. However, if the group does not progress beyond this stage of “how we are the same,” little is gained from the experience. After all, if we are the same, why leave home and come to the school? It is therefore a very tricky challenge for the organizers and staff to slowly move the group to accept their differences and recognize that they can still be a group despite their differences.

Finally, the “generalization of trust,” or, given the extremely limited circumstances, the generalization of some rules to allow an experience held in common (or, in the Deweian sense, of shared experience) is the challenge of the school. I think that every year this is up for grabs and its success is nowhere assured. Every year the extent to which this is achieved and the extent to which this is achieved in relation to the willingness to recognize real, constitutive difference is somewhat different—but this is the real lesson of the school. The extent to which this is accomplished (and we see that it can be accomplished) is the success of the school and its unique pedagogy.

The long-term success of the school will be measured (with time) in terms of its ability to bring a certain (even small) percentage of the fellows to duplicate this analytic exercise (not necessary the content or form) in their host countries and in programs that they are already working on (whether in the field of education, law, religious/community development, etc.). We are perhaps a long way from knowing how to do this, but the 2008 school in Birmingham, UK which will put in place local (in-site) structures to further these aims indicates a very good start in this direction.

Author Bio

Adam B. Seligman is Director of the International Summer School on Religion and Public Life. He is also Professor in the Department of Religion and Research Associate at the Institute on Culture, Religion and World Affairs, at Boston University.

[i] Dewey, John. 1916. The Control of Ideas by Facts. In Essays in Experimental Logic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 239.

[ii] Dewey, John. 1997 [1910]. How We Think. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p.13.

[iii] This is why it is so important for the participants to have a modicum of trust among themselves, to grant one another some “moral credit.” This takes the form of sharing their beliefs and assumptions about the other, as well as on present conditions in a manner in which “outsiders” can witness the debates and conflicts among “insiders” (Muslims witnessing acrimonious debates between observant and less observant Jews, Jews and Christians witnessing debates between those who claim to be Muslims and those who refuse to admit a certain group to the Muslim fold).

[iv] Note that the tribe at any given moment is not coterminous with the tradition.

[v] Dewey, John. 2004 [1916]. Democracy and Education. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 134.

[vi] Dewey, Democracy and Education, p. 137.

[vii] Milner, Marion. 1952. Aspects of Symbolism in Comprehension of the Not-Self. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 33: 181-95. p. 182.

[viii] Jones, Ernest. 1948 [1916]. Theory of Symbolism. In Papers on Psychoanalysis. London: Maresfield Reprints.

[ix] Milner, Acts of Symbolism in Comprehension of the Not-Self, p. 279.

[x] We may add here that the key feature of tolerance is precisely the suspension of judgment. When one tolerates what one finds distasteful or wrong one in effect suspends a final judgment on such acts rather than accepts them as right or beneficial (in which case tolerance would not be necessary).

[xi] Dewey, How We Think, p. 109.

[xii] Dewey, How We Think, p. 105–6.